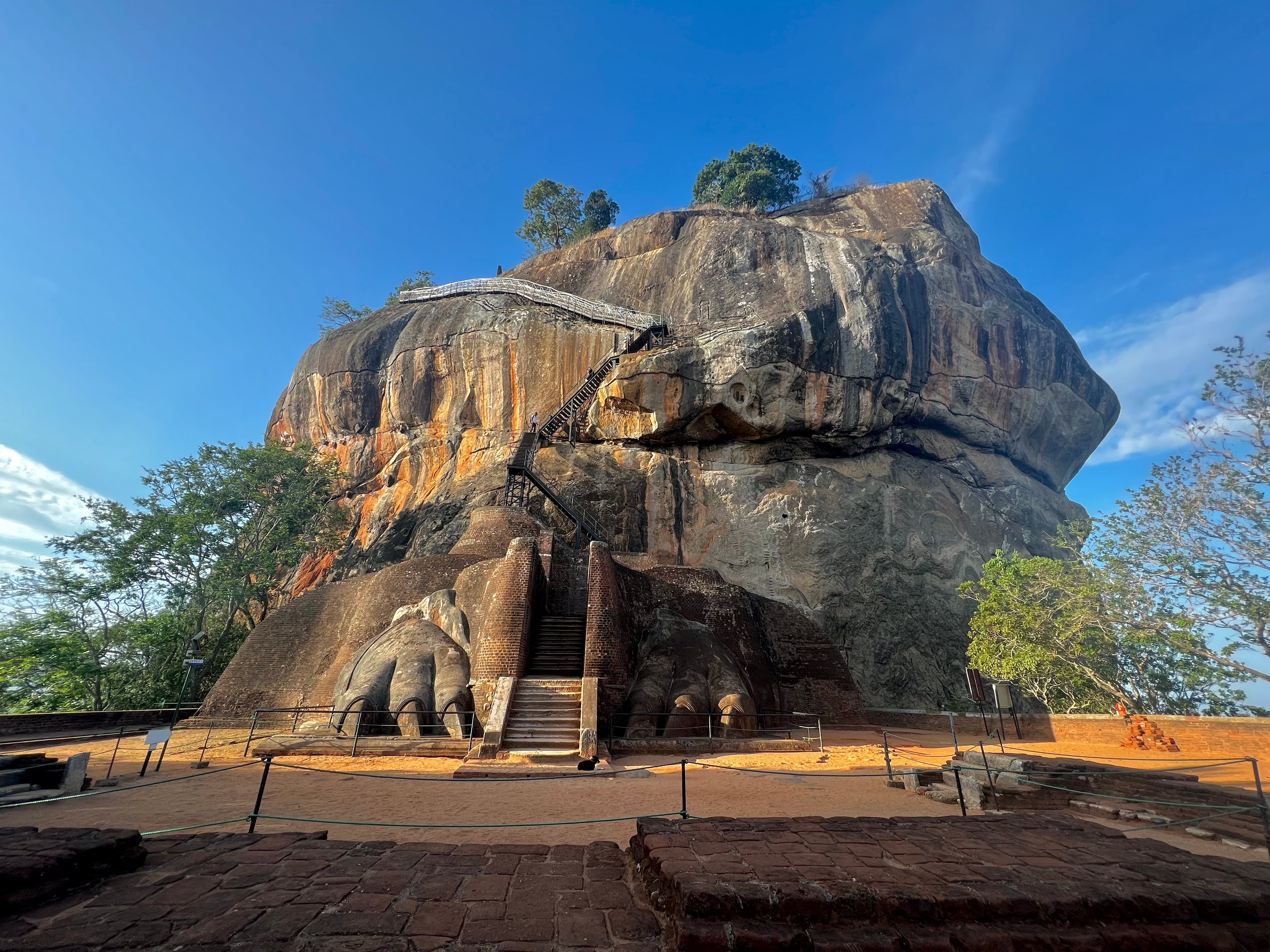

It was 7am on a Tuesday and I was staring at pictures of naked ladies after climbing up an ancient rock fortress in Sri Lanka. Known as the Sigiriya Damsels, the voluptuous women were painted onto the walls of Sigiriya’s Lion Rock about 1,500 years ago, and are the crowning feature of a gut-wrenchingly beautiful climb. I started the journey early, walking with no one but a handful of local monkeys and a chorus of birdsong for company, sunrise cloaking the towering mound in a pastel glow, then bursting into golden light as I reached the summit.

A year before, it would have been hard to imagine standing in that spot. But there I was, celebrating the country’s reopening to tourists.

Sri Lanka has endured a tough few years. In 2022, it saw its worst economic emergency since gaining independence from Britain in 1948, which coincided with widespread power cuts and fuel shortages. The rate of inflation for the year was calculated as 50 per cent; the average yearly inflation rate before then had been 8.9 per cent since 1960. Several factors were behind the crisis, including the Covid-19 pandemic. It decimated tourism, one of Sri Lanka’s largest foreign exchange earners and an essential cog in the country’s economy, which compounded a decline in visitors that started in 2019 following a series of bomb attacks.

But things are on the up. The opinion across the board is that Sri Lanka is now past the peak of its crisis – and it’s time for tourists to return. And they are. Sri Lanka is hoping to welcome 1.5 million visitors by the end of the year and looks on track to hit that, welcoming its millionth visitor this September. “It’s been extremely tough but we’re a resilient nation,” says Chaminda Munasinghe, my guide for the trip. “Now we’re recovering, and tourism is the catalyst.”

Another vote of confidence has come from Qatar Airways, which flew 65 per cent more UK passengers to Colombo between January to September this year than in the whole of 2022. The airline resumed its route from Birmingham Airport in July, and flights are noticeably cheaper than flying from London, despite Birmingham only being an hour by direct train from the capital; think economy prices from £450 rather than £750. The Indian Ocean island has already become one of the airline’s most popular destinations from the Midlands.

It’s easy to see why Britons have a soft spot for Sri Lanka. It offers an adventure, but there are enough touches of home to make it strangely comforting. They drive on the left; plug sockets don’t need an adapter. On arrival at Colombo Airport, a welcome party placed a string of fragrant flowers around my neck – then poured a cup of strong, milky tea out of a fine china pot that would send my granny wild with envy.

The British also love a good deal, and in Sri Lanka there is real affordable luxury on offer that might surprise. “It’s not known for luxury, but it’s there and it’s amazing value,” said Chaminda. As we pootled through the capital, he told me that the most expensive room in the city can be found at the Shangri-La – £400 a night for a private apartment. In comparison, entry-level double rooms go for £800 in the Shangri-La’s London outpost.

That’s not the only Sri Lankan surprise. It’s a brilliant safari destination, with one of the highest rates of unique biodiversity in the world and 16 endemic species, including both the Sri Lankan leopard and elephant. The latter is the largest of the Asian elephants, making them the biggest land animal on the continent – coupled with their preference for moving in large groups, sightings are made incredibly easy.

I spied 60 of them in Minneriya National Park, which lies in the centre north of the island, and a 25-minute drive from the Jetwing Vil Uyana, where I stayed for two nights. Inspired by the London Wetlands Centre, in the early 2000s the hotel group converted 28 acres of abandoned land into a flourishing private reserve. It’s now Sri Lanka’s most successful ecotourism initiative and features a collection of luxury villas sprawled over paddy fields and reed beds. Guests can take wildlife walks to meet their neighbours, which include tiny slow lorises and a thankfully ‘incurious’ crocodile in the marshes. Their starting rate in summer is $325 (£260) a night for a private dwelling with an open-air courtyard.

According to Chaminda, there’s no real “peak” or “off” season in Sri Lanka. Unusually, the country is never fully in rain: in the southwest, the monsoon runs from May to August, while in the north it’s December to March. I experienced this first hand. In northern Vil Uyana, I got glorious sunshine, drinking £3.50 happy hour cocktails by the pool. Then, after just two hours in the car, I’m heading south through Kandy into a lingering intermonsoon downpour, peering at drenched hills out of the window.

As I climbed higher into Sri Lanka’s tea plantations, the rain only added to the atmosphere. On a tea factory tour, the metallic clang of droplets hitting the roof blended with the voice of our guide. Later, at The Grand Hotel, I was met with a steaming bowl of soup as my “welcome drink”, to ward off the chill outside as I checked in.

This hill country hotel is in Nuwara Eliya, an area known as “Little England” thanks to its red postboxes and houses that could have been plucked from the UK’s Lake District. The Grand is no different, looking like a lakehouse in Ullswater – only with leopards nearby. The Queen came for tea here in 1954 on her first official visit to a Commonwealth country, and it still retains a regal edge as a place to drink the beverage Sri Lanka is famous for. There’s a room lined with tea tins and plans for a tea sommelier, who’ll mix a perfect brew for you on a bespoke cart: a Sri Lankan version of The Connaught’s martini trolley.

It’s not just the weather that changes: each place I visited had its own distinct smell. I spent my first night in Hotel Colombo at Mount Lavinia, a 200-year-old structure that’s the only hotel in the city with a private beach. “It smells like Christmas,” I told the porter as we walked to the room. “We rub the wood with clove oil,” he replied. At the Jetwing Vil Uyana, everything hums with lemongrass, a natural bug deterrent, while the tea factory in the hills smelt like stepping into a box of Twinings’ breakfast blend.

I finished my trip at Cape Weligama Resort, a Relais & Chateaux property situated on the south coast near the fortified old city of Galle. The most expensive hotel of the visit, it’s still a far cry from luxury prices elsewhere. Even the lowest category of rooms come with private, sun-soaked gardens or verandahs, freestanding stone bathtubs, in-room steam rooms and on-call butlers, but you can get room rates starting from £390 this November.

Designed to feel like a traditional Sri Lankan village, opulence whispers from terracotta-roofed buildings strewn amid tropical gardens and private infinity pools dotted throughout. Pathways to the rooms, restaurants and pools feel intimate, closed in by lush greenery, but hidden doors open into immense spaces. My Premier Villa, still less than £500, was just under 2,000 square feet – a footprint multiple times bigger than my south London flat.

It was a final flavour of Sri Lanka, a country that, in the space of a week, had shown wildlife-filled savannahs, hills shrouded in mist, and now beaches so soft they looked as if they were melting into the water. “We’re compact but diverse,” explains Chaminda. “A small nation filled with so much to explore, there’s no way to ever see it all in one go. You just have to return, again and again.” I plan to do just that.

Travel essentials

Getting there

Qatar Airways operates flights to Colombo from London, Birmingham, Edinburgh and Manchester airports.

Staying there

Jetwing Vil Uyana is ideally placed to visit Sigiriya and allows guests to experience modern luxury while remaining close to Sri Lanka’s wildlife.