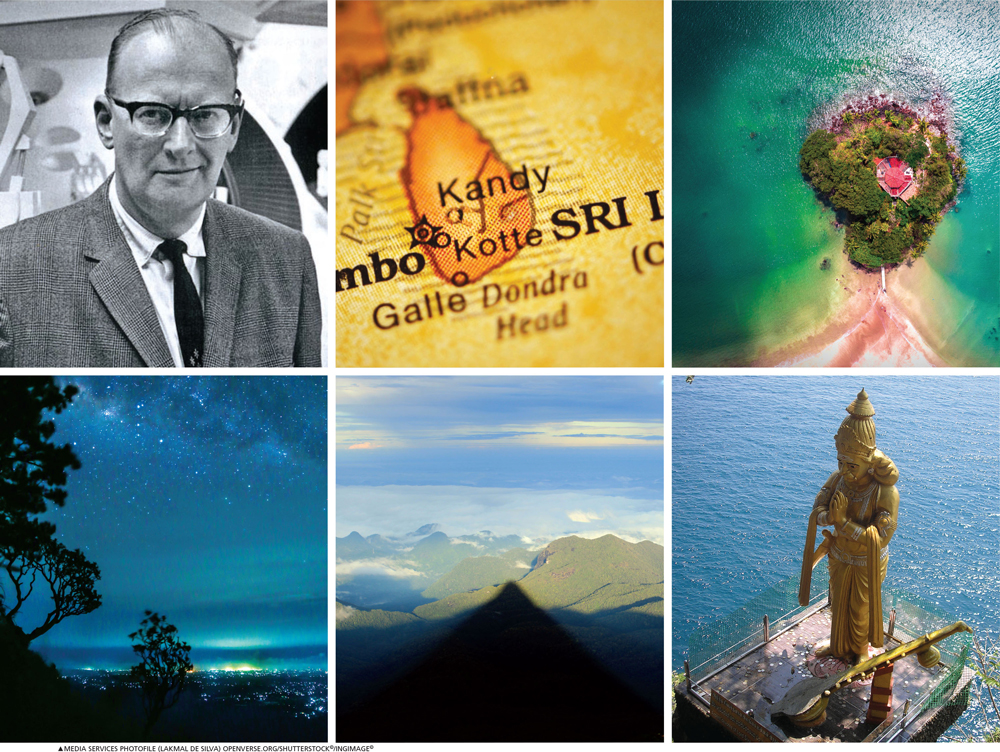

AN ISLAND IN HIGH ORBIT

Wijith DeChickera takes a ride in the space elevator for the satellite’s eye view of the late Sir Arthur C. Clarke’s perspective of and legacy to Sri Lanka

The first map Sri Lanka appears on was drawn by Greek cartographer Eratosthenes in 194 BC where the island named Taprobanā is at India’s southern tip. Then there was Egyptian astronomer, mathematician and geographer Claudius Ptolemy who identified Taprobanē in 139 AD as being a large island south of continental Asia.

There was a third charterer – of dreams as yet undreamed – who built on the work of the ancients to put Sri Lanka on the modern map. Quoting Alfred Lord Tennyson: “I dipped into the future, far as human eye could see; saw the vision of the world and all the wonders that would be…”

Arthur Charles Clarke was that dreamer. And by the time he and legions of fans explored the fantasies of a space age Sri Lanka, the renowned writer – once considered part of sci-fi’s ‘big three’ along with Isaac Asimov and Robert Heinlein – would be honoured by the country of his adoption and establish his reputation as a prophet.

Clarke discovered Taprobane almost serendipitously. While on a Colombo-side day stopover en route to Australia in 1954, he fell in love with the island’s laid-back way of life.

Vowing to return, the traveller with a first-class degree in mathematics and physics from King’s College London emigrated from England and took up Sri Lankan residency in 1956, where he later became Chancellor of the University of Moratuwa (1979-2002).

Diver, underwater explorer, author, scholar, science promoter, technology buff and visionary, Clarke lived in Serendip until his death in 2008, by which time the man who was demonstrably Sri Lanka’s most famous resident guest had been bestowed the island nation’s highest honour – Sri Lankabhimanya – despite giving politics a wide berth… although he was on cordial terms with national leaders.

While his fame and fortune grew along the trajectory of voluminous writings on space exploration science fiction, Clarke’s abiding passion was beneath the waves of the Indian Ocean’s island pearl. Since his initial advent to its shores, Arthur was often underwater – pursuing his lifelong interest in scuba diving.

First entertained for purely personal pleasure, this hobby was to bring Clarke a modicum of popularity with the maritime community, following a 1956 (his very first year in our tropical paradise) discovery of the ancient and original Koneswaram Temple’s submerged ruins off Trincomalee’s aquamarine waters.

Clarke described that adventure in his 1957 book The Reefs of Taprobane. Popularity with divers led to the founding of a small diving school and opening a dive shop near Trinco.

Despite residential entrepreneurship around several of Sri Lanka’s touristy coastal towns (Clarke lived for a while in Unawatuna and then Colombo, and often dived in Hikkaduwa and Nilaveli), his legacy to the land he loved was to launch it to the stars.

However, it was as a prolific writer of sci-fi that he was able to showcase Sri Lanka in its best light.

In The Fountains of Paradise (1979), a stupendous reimagining of the Kashyapa legend, Clarke located in the mists of time past a religious war between a renegade king garrisoned at Sigiriya, pitting his wits against the intransigence of authoritarian monks nestled atop a ‘high holy hill’ that was clearly the island’s unmistakeably conical mountaintop Adam’s Peak.

The brilliance of his narrative in shuttling between past and future – where the isle is the location of a space elevator, a pet project of this prophetic visionary – highlighted not only an iconic mountain and a legendary rock fortress but also promoted Sri Lanka as the possible future locale for an innovative engineering marvel.

A brainchild of pioneering Russian engineer Yuri Artsutanov, the space elevator received a figurative boost into orbit through Clarke’s numerous mentions of the invention – including in a poignantly penned The Songs of Distant Earth (1986) where the island of Thalassa, another tropical paradise – albeit on an alien planet colonised by humanity’s spacefaring descendants – is indubitably Serendib in evocative disguise.

From promoting Rumassala where the Earth’s gravitational field is remarkably lower than elsewhere on the planet as a site for the space elevator to hymning the island’s sunken aquatic treasures, Clarke was unapologetically a champion of “this other Eden, demi-paradise.”

An epitaph on the grave of an unknown astronomer reads: ‘I have loved the stars too fondly to be fearful of the night.’ Sir Arthur’s could easily replace ‘stars’ with ‘Sri Lanka’ and ‘night’ with the terrifying picture that our post-bankruptcy milieu paints.

It was as a prolific writer of sci-fi that he was able to showcase Sri Lanka in its best light