THE CLIMATE CLOCK IS TICKING

Samantha Amerasinghe highlights the need for policy makers to act urgently

The effects of the climate crisis are being felt everywhere. Extreme temperatures causing record-breaking heatwaves have wreaked havoc around the world this year, turning the spotlight on how vulnerable many sectors of the economy are to climate change.

And the economic impact of what experts warn could be a new era of intense heat will be significant; it will go well beyond tourism to affect industries and sectors including construction, manufacturing, agriculture, transport and insurance.

Industries will need to brace for changes in the way they do business as high temperatures become more common due to the fallout from climate change.

Climate change will be a drag on productivity and consequently, losses will be detrimental to growth. An ILO study predicts that by 2030, the equivalent of more than two percent of working hours worldwide will be lost annually due to the slower pace of work brought about by extreme heat conditions.

A Dartmouth study published last year found that heatwaves brought on by human induced climate change cost the global economy an estimated US$ 16 trillion over a 21 year period from the 1990s. These costs are likely to spiral in the decades ahead as economies reorient themselves to mitigate the risks and disruptions that extreme heat will cause.

Climate change will have far-reaching consequences for many industries and economic sectors. According to the International Labour Organization, outdoor workers – especially those in agriculture and construction – are particularly at risk of death or sickness and reduced productivity due to heat exposure.

As heatwaves become more frequent however, workers in factories and warehouses without air conditioning will also be at risk. The poorest will suffer the most as productivity losses triggered by extreme heat are often concentrated in jobs where wages tend to be lower than average.

Beyond the impact of extreme heat on the workforce, many industries are being forced to rethink existential issues such as where they’re located and how they operate.

Construction is one industry that may need to reinvent itself as extreme weather conditions not only affect work on sites but also materials such as steel and concrete. This could lead to additional costs for the industry and drive prices up in the process.

Manufacturing is another area that faces significant challenges.

In the case of agriculture, extreme heat can result in reducing crop yields, which in turn will fuel rising prices and food insecurity.

The risk to infrastructure from heat stress on railway tracks, roads and airports is also a concern. As work becomes riskier in a range of sectors moreover, insurance costs will rise.

Policy makers will need to act now to prepare for extreme heat as catastrophic weather events including heatwaves will undoubtedly become more frequent and intense. In July, average temperatures were at least 1.1°C hotter globally than preindustrial levels.

Record high temperatures were noted from China to Italy – with the former recording temperatures as high as 52.2°C in its northwestern Xinjiang Province. The US also endured a long-lasting heatwave that affected as many as 100 million people in the south, as well as flooding in the northeast. Southern Europe also struggled with extreme heat.

Internationally, adaptation is expected to be high on the agenda at the UN Climate Change Conference of the Parties (COP28) climate negotiations in Dubai in November as it’s increasingly evident that time is running out on climate change.

Politicians are looking at how money can be raised to help countries – especially those in the Global South – deal with extreme temperatures.

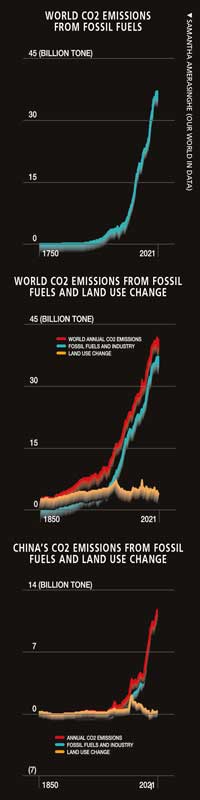

The US and China, which are the world’s biggest polluters, have resumed climate talks after a long hiatus due to bilateral tensions in the hope that progress will be made ahead of COP28. Both countries have agreed to work towards guaranteeing a positive outcome.

Cooperation between America and the People’s Republic is critical to addressing the reduction of methane emissions, and helping the two countries develop new Paris Agreement linked targets to be submitted in 2025.

According to the World Bank, China is responsible for 27 percent of global CO2 emissions and a third of the world’s greenhouse gases.

Though this is far more than the US and EU, its emissions are lower on a per capita basis. In 2020, Chinese President Xi Jinping pledged that his country would reach peak emissions by 2030 and be carbon neutral by 2060.

Central banks are under increasing pressure to explain how far they should use their powers to aid the fight against climate change. More freak weather and rising temperatures threaten further economic shocks.

Until now, central banks have been able to manage short-lived weather effects without adjusting policy.

As extreme weather becomes more frequent and the global climate gradually becomes warmer however, economic shocks could be more persistent and harder for policy makers to ignore.

The climate clock is ticking – and policy makers must act now!