WATERSHED YEAR AHEAD?

Shiran Fernando looks back on 2003 and forward to 2024 as the national economy takes centre stage

Year 2023 could be described as one of relative stabilisation for the economy after a host of economic shocks and shortages, following the social and political crises in 2022.

Sri Lanka managed to secure its 17th IMF programme 2023, which helped unlock financing from multilaterals such as the International Monetary Fund and World Bank while improving the nation’s fiscal status.

However, stabilisation has also meant weak growth.

So could 2024 be a year of reform and growth to complement the stabilisation – or another year of missed opportunities?

KEY INDICATORS After a steep depreciation of the rupee from Rs. 200 against the US Dollar to over 360 rupees, 2023 saw an appreciation of close to Rs. 300 and then a gradual depreciation to the 330 rupee level in late November.

Improvements in remittances, as well as tourism and financial inflows to the local bond market, along with the finalisation of the IMF’s programme in March, aided this appreciation.

Growth in the first half of the year was weak, contracting by 7.9 percent. Data for the second half of 2023 is yet to be published but Sri Lanka’s economic performance is expected to be better with improvements in agriculture and services.

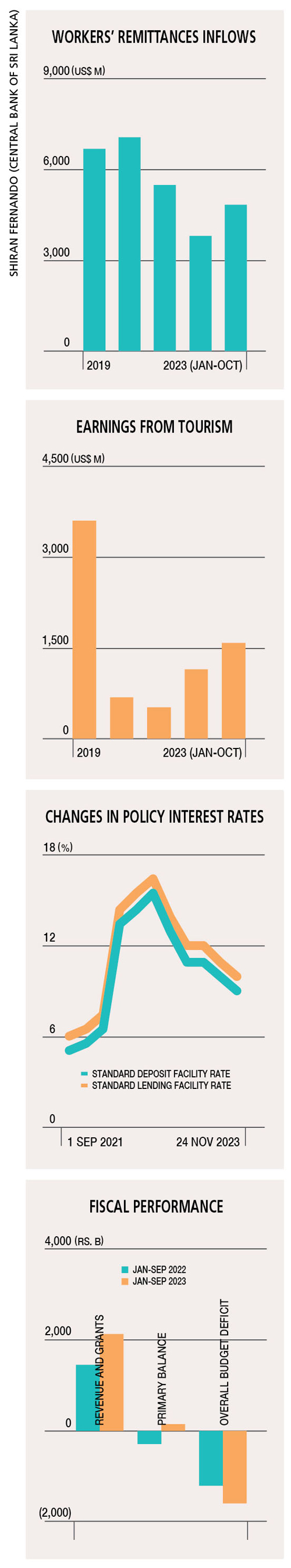

Year 2022 saw a sharp rise in monetary policy rates in response to the high level of inflation – by September 2023 however, headline inflation based on the Colombo Consumer Price Index (CCPI) declined from 70 percent to 1.3 percent.

This enabled the Central Bank of Sri Lanka to reduce monetary policy rates by 6.5 percent; and the prime lending rate fell from nearly 30 percent in early 2023 to around 13 percent.

New legislation provides the Central Bank with more independence and allows it to shift to an inflation targeting framework. It will also limit governmental dependence on the bank to finance the budget deficit through monetary printing.

The most positive development has been a change in the fiscal status.

According to the Ministry of Finance, the country registered a primary budget surplus of Rs. 123 billion in the first nine months of 2023 compared to the target of a deficit of 160 billion rupees under the IMF programme.

Total revenue rose by 46 percent, aided by a 51 percent increase in tax revenue.

The reserves position also improved from a low of US$ 1.8 billion in mid-2022 to about 3.6 billion dollars by the last quarter of 2023. This was partly due to the pause in external debt repayments with restructuring taking place vis-à-vis international creditors.

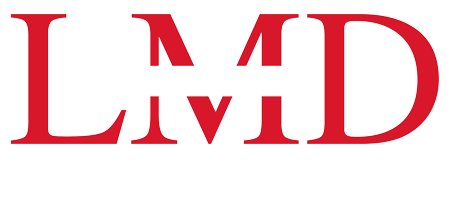

Tourism and workers remittances also improved in 2023. Remittance inflows grew by 66 percent in the first 10 months of the year compared to 2022 while tourism earnings increased by 72 percent during the same period. This helped negate the 10 percent slowdown in exports due to weak external demand.

WAY AHEAD IN 2024 The focus will be to maintain stability and accelerate growth through reforms. Once external debt restructuring is complete, key reforms related to trade, land and state owned enterprises (SOEs) can help catalyse growth.

While progress was made in terms of these aspects in 2023, the material benefits are yet to be experienced by the public. For instance, SOE reforms need to see the completion of at least two transactions in the first half of 2024 under the transparent process that’s being pursued.

This will not only generate interest from foreign investors – in particular, for the hotel and hospital sectors, which will be addressed in the first round – but also help dispel the notion that the country is selling off its assets.

While taxes such as value added tax (VAT) are to increase by three percent (to 18%) with many exemptions removed, the impact on inflation and demand for these items remains to be seen. Household consumption expenditure (about 60% of growth) has been contracting, similar to GDP, since 2022.

Welfare policies in the national budget for 2024 (an increase in public sector allowances and tripling of the welfare scheme allocation) could increase disposable incomes and this may support higher consumption volumes during the year.

However, it is unlikely that this will stimulate a high import cycle similar to what the country experienced in 2011 and 2015.

The shift to inflation targeting by the Central Bank, and allowing the currency to float, will depend on the credibility and independence of the institution. This will be tested during the year in terms of how much further monetary policy will be used to stimulate growth and the demand for credit.

ELECTION YEAR A key risk lies with the prospect of elections in 2024.

Any deviation in the fiscal trajectory pre or post-elections could derail the existing IMF programme and path to debt sustainability.

The impact of global conflicts on commodity prices will also need to be addressed.