Reuters – July 28, 2023

China faces a long slog to artificial intelligence supremacy. It wants to be a leader in the field by 2030 and this month unveiled new rules governing the technology that are less onerous than expected. But closed online ecosystems, Beijing’s controls on internet content and U.S. curbs on semiconductor exports to the world’s second largest economy will hamper progress.

There were high expectations of what the People’s Republic could achieve with the technology seen as having the power to solve some of the most pressing challenges on the planet. “In the age of AI, where data is the new oil, China is the new Saudi Arabia”, venture capitalist Lee Kai-fu declared in 2018. Reasons for confidence included troves of data spanning everything from digital payments to e-commerce as well as government support and a growing army of entrepreneurs. Fast forward to today and things look far less compelling.

China’s latest regulations on generative AI – where algorithms trained on vast datasets and users’ inputs learn to perform complex tasks – will pave the way for its tech champions to launch products to rival OpenAI’s ChatGPT. Under the new policy set to go into effect next month, providers of services to the public must submit security assessments. That implies that national security concerns will restrict the technology’s evolution and will pile more pain onto an industry President Xi Jinping has targeted in a brutal two-year crackdown aimed at curbing the disorderly expansion of capital.

The scope and requirements are stricter than in other regions like the United States, where voluntary codes of conduct and rules are only starting to be considered. The European Union, for example, is trying to push ahead with legislation primarily targeting “high risk” AI applications such as those that can be used to influence election outcomes and platforms that have over 45 million users. Yet compared to China’s earlier April draft which contained near-impossible demands such requiring AI-created content to be true and accurate, the latest version seems practical and signals Beijing is serious about supporting the nascent sector to some extent. Notably, the new rules only apply to consumer-facing services, suggesting business products might be given more latitude.

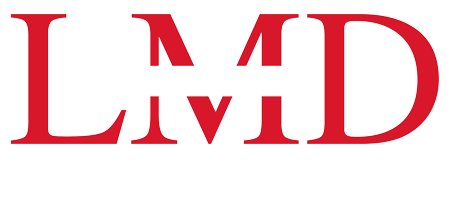

That should benefit outfits like search-engine operator Baidu (9888.HK), , the first major Chinese company to come up with an answer to ChatGPT. Analysts at Goldman Sachs reckon the $50 billion group led by Robin Li will be among the first batch of applicants to win approval to commercialise its chatbot, currently in testing phase, and estimate AI products can boost annual revenue by 13% in 2025. Baidu’s New York stock is up by 30% this year, outperforming the 9% rise in the Nasdaq Golden Dragon index of U.S.-listed Chinese companies.

Yet the country also faces a unique set of challenges. Washington may soon tighten export restrictions to China by targeting AI semiconductors, according to the Wall Street Journal. Cutting off access to chips sold by Nvidia (NVDA.O) or AMD (AMD.O) might set Baidu and peers back by years. Moreover, the country may have leapfrogged the West in mobile payments and such, but China’s internet is dominated by a handful of giants that have built up walled gardens, where platforms keep information and user data to themselves. That means different companies will have access to very different types of data. That’s one reason Bernstein analysts peg Tencent (0700.HK) and ByteDance, whose social media and video apps have the largest reach in the country, as the most promising AI contenders.

There are other hurdles companies must navigate. Strict censorship requirements are one. China’s internet firewall that prohibits its citizens from accessing unapproved content will limit the amount of information companies can use to train their AI models, potentially leaving firms in the country at a disadvantage to Western peers.

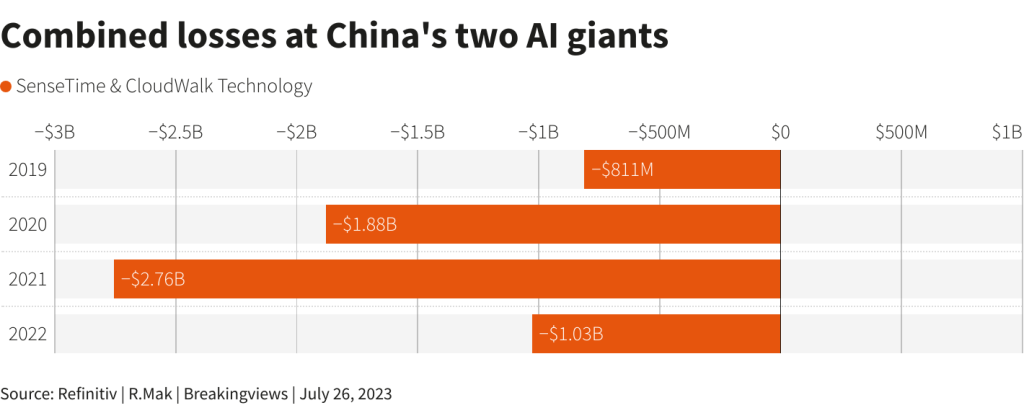

Another headscratcher is how to make money. Microsoft (MSFT.O) recently said it will charge $30 a month for generative-AI features in its widely-used office software. It’s hard to see how Chinese software or cloud providers like Alibaba (9988.HK), can charge premium prices to mainland businesses which lag by far their global counterparts when it comes to IT spending. Cumulative losses at the Alibaba-backed Megvii, which is preparing to go public in Shanghai, topped $1.8 billion between 2018 to 2020; listed peers SenseTime (0020.HK) and CloudWalk Technology (688327.SS) remain deep in the red too. A slowing economy and brutal price war in the fiercely competitive cloud market will only make monetising AI products harder.

Perhaps the biggest uncertainty is whether Xi will allow the private companies currently leading the charge in AI to thrive. It would be at odds with his government’s efforts to strengthen control over certain industries over the past few years. While officials are now reassuring investors that the environment for entrepreneurial businesses will improve, licensing requirements and the latest AI rules suggest Beijing will keep a tight grip over the sector and views it as highly strategic. That might best explain why U.S.-listed Alibaba in May announced plans for a full-separation of its cloud and data business. China’s AI moment has arrived, only with far less promise than initially hoped.