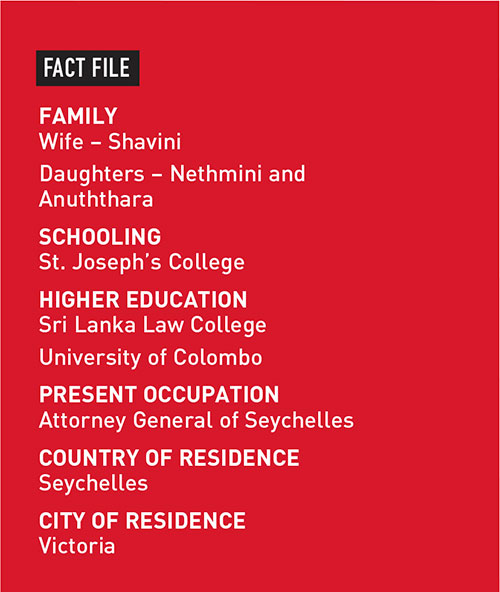

Vinsent Perera

Moral values and ethics are antidotes for corruption

Vinsent Perera was appointed Attorney General of Seychelles in October last year, having served as a legal consultant and the Head of Civil Litigation at the Attorney General’s Office.

He previously served as a judge of the court of appeal and high court of Fiji, the Assistant Director of Public Prosecutions in Fiji, the Head of the Legal Department of the Fiji Independent Commission Against Corruption (FICAC) and a state counsel of the Attorney General’s Department of Sri Lanka.

Perera is also an attorney-at-law of the Supreme Court of Sri Lanka, and a barrister and solicitor in Fiji. He is an accredited mediator too.

He holds a master of laws degree from the University of Colombo.

Lawyers and judges need not only a good knowledge of law but also exceptional people skills – particularly empathy, an understanding of human behaviour and above all, an exceptional moral compass

Q: With over two decades of experience across multiple jurisdictions, what inspired you to pursue law?

A: I have had the opportunity of experiencing the adversarial legal system from multiple perspectives – as a state counsel, prosecutor, judge and defence lawyer. Yet, I do not have a particular personal story that motivated me, save for saying that it was the universe that guided me to enter and remain in law.

I must also add that my seniors at the Attorney General’s Department of Sri Lanka moulded me to be the legal professional I am today.

Q: Having served in Sri Lanka, Fiji and the Seychelles, how has working in different legal systems influenced your perspective on justice and governance?

A: I’ve realised that the root cause of any case or dispute in any jurisdiction is often one or more of the seven deadly sins – pride, greed, lust, envy, gluttony, wrath and sloth – or if you dig deeper, the three unwholesome roots of greed, hatred and delusion.

The permanent solution to injustice and bad governance is within each of us. If every citizen – including those in executive, legislative and the judiciary positions – strives to become a good human being justice and good governance will prevail.

Of course, dealing with the seven deadly sins or the unwholesome roots is the main spiritual challenge for any human being. Yet, little or no focus is made to encourage and guide citizens to overcome these evils.

Lawyers and judges need not only a good knowledge of law but also exceptional people skills – particularly empathy, an understanding of human behaviour and above all, an exceptional moral compass.

I believe that civil disputes between private parties should be resolved through alternative dispute resolution (ADR) mechanisms, particularly mediation.

Meanwhile, in criminal matters legal systems focus on safeguarding the rights of the accused – which should indeed be the case. But adequate importance is not given to the victims and their rights. So more focus and effort is needed to make the courts environment friendly or unintimidating for victims of crime.

Q: The legal profession is evolving with advancements in technology, AI and digital justice systems. How do you see these trends impacting the legal sector in the Seychelles?

A: With the Industrial Revolution, technological advancements – while making human life easier – led to complex legal issues and disputes.

We saw how the COVID-19 pandemic forced many jurisdictions, previously unprepared, to adopt digital justice measures such as online filing and virtual hearings. In fact, the pandemic was responsible for accelerating the process of technology becoming an indispensable part of human life in many countries.

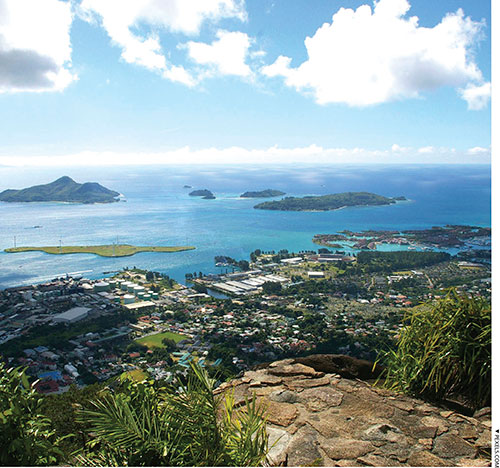

For instance, Seychelles is now in the process of transforming the justice system with the assistance of technology.

However, technology remains an ambivalent friend.

Today, technology has taken criminal behaviour to unprecedented levels. It has forced the legislature to pass relevant laws and law enforcement agencies, and prosecutors to acquire relevant skills and knowledge, to fight against cybercrime and protect citizens.

In my view, legal education – including in Sri Lanka – focusses on legal knowledge and skills rather than producing the ultimate ‘good’ lawyer

Q: ADR is growing globally. How do you see its role evolving in the Seychelles – and can Sri Lanka adopt similar models to improve its judicial backlog?

A: Despite the absence of a comprehensive legal framework for ADR in the Seychelles, the judiciary is actively promoting its use to assist in the disposal of cases.

Sri Lanka on the other hand, has a good legal framework for ADR.

I’m a strong supporter of ADR. In my view, all civil disputes – especially those between private parties – should be resolved through ADR mechanisms such as mediation.

The court will ultimately decide the winner and loser in a case, leaving the dispute unresolved or even aggravated. Through mediation however, parties can be guided to resolve a dispute for good, where both become winners.

Q: What are your thoughts on legal education and training in Sri Lanka?

A: People seek the assistance of lawyers because they are suffering – often as a result of their own inner evils or those of the other party to the dispute.

Although what’s being presented are the consequences, what a client would seek is a solution to end the suffering. A lawyer cannot truly end the suffering of a client by only dealing with the consequences without tackling the root cause of the problem.

So to properly serve a client, a lawyer should have not only knowledge and skills in the law but also a deep understanding and control over inner evils, as well as a strong moral compass. In other words, a lawyer should be ‘good’ in every sense of the word.

In my view, legal education – including in Sri Lanka – focusses on legal knowledge and skills rather than producing the ultimate ‘good’ lawyer.

Q: As a key hub in the Indian Ocean, what legal steps should Sri Lanka take to strengthen maritime law and regional security?

A: The maritime legal framework in Sri Lanka is quite comprehensive and structured around key international conventions.

Sri Lanka has jurisdiction to hear cases involving piracy offences in respect of ships registered in the country. However, Sri Lanka was not able to prosecute the case of a Sri Lankan vessel and crew allegedly abducted by Somali pirates in January 2024.

Therefore, I can safely say that Sri Lanka’s approach to piracy is an area that has room for improvement.

Q: How can Sri Lanka improve investor confidence through legal and regulatory reforms?

A: The rule of law in a country is fundamental to investor confidence. As part of the due diligence process to determine whether an investment would be at risk, a potential investor would examine the law and order situation of the receiving country.

In this regard, it is important for Sri Lanka to implement necessary reforms such as ensuring investment protection, promoting anticorruption measures, implementing efficient and effective dispute resolution mechanisms, removing unnecessary red tape and aligning with international financial standards.

Steps taken to accelerate Sri Lanka’s digital transformation will increase its competitiveness and boost investor confidence.

Q: With globalisation and increased digital transactions, how should Sri Lanka update its legal framework to address cybercrime, digital governance and AI regulation?

A: Sri Lanka is a State Party to the Budapest Convention on Cybercrime.

The next step would be to join the recent United Nations Convention on Cybercrime, adopted in December last year. Given the nature of the threat, international cooperation is essential to combat cybercrime. Sri Lanka also appears to be working on strengthening digital governance and AI regulation.

The United Nations General Assembly has adopted a resolution on AI and the European parliament has passed the first AI Act. These instruments will assist Sri Lanka in shaping its own legal framework on AI regulation.

If not properly dealt with, corruption can bring a country to its knees. It cannot be eradicated or minimised through legislation alone – I would say moral values and ethics are antidotes for corruption

Q: Based on your experience in Fiji and the Seychelles, what lessons can Sri Lanka adopt to combat corruption and strengthen legal accountability?

A: I strongly recommend that the offence of Abuse of Office be introduced in Sri Lanka. This is a very useful tool in the fight against corruption.

The offence is committed when a person employed in public service performs an arbitrary act prejudicial to another, in abuse of the authority of his or her office.

Moreover, there should be a designated corruption court to deal with related cases. Provisions should also be made to have regular trials for such cases.

Q: What role do you think the private sector and corporate governance play in ensuring legal transparency in Sri Lanka?

A: Transparency is a key element of the rule of law. Bribery and corruption undermine the rule of law. Bribery and corruption in the public sector often take place with the complicity of the private sector. Therefore, it is crucial for the private sector to uphold zero tolerance toward the same.

It would also be necessary to strengthen corporate governance by promoting transparency and accountability, establishing proper monitoring and reporting mechanisms, and implementing policies that promote a zero tolerance stance on bribery and corruption.

Q: If you were to return to Sri Lanka’s legal system in a leadership role, what area would you prioritise for legal reform?

A: It would be anticorruption. If not properly dealt with, corruption can bring a country to its knees. It cannot be eradicated or minimised through legislation alone – I would say moral values and ethics are antidotes for corruption.