TRIP THE LIGHT FANTASTIC LRT

Wijith DeChickera takes a ride in suburbia and comes to the halting conclusion that Sri Lanka’s railways need serious elevating – literally

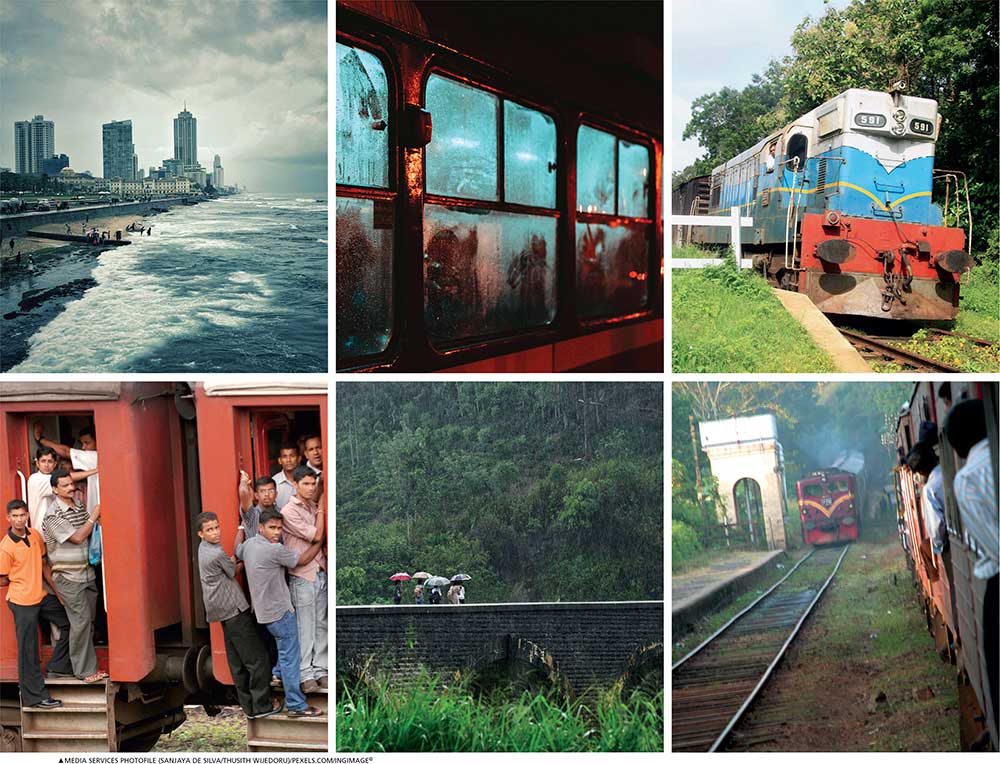

It is dark overhead. A light drizzle threatens to turn into heavy weather. The southwest monsoon searches for somewhere to unleash its burden. Cloud banks pregnant with rain hover ominously over the coastline. A westerly breeze whips up anxiety. Even the umbrellas of after work commuters are no safeguard against deluges. The railway station’s platform is awash with bowed and bent people waiting for a train.

Of course, it is late… and inevitably packed. Despite creaking at the seams, it winds slowly to a stop at one of many halts on the down line, teeming with wet or irate passengers. A mad scramble to board the long metal monster ensues.

It’s a minor miracle that no one is trampled underfoot in the pell-mell dash for the least overcrowded compartment. Latecomers have to settle for the footboard where they brave the pelting downpour.

They cling on for dear life in-between stations, agonising minutes apart. And in the case of expresses, they remain precariously perched – muscles on fire, tendons straining for a safer grip – for quarter hours at a time… in the case of yon long-distance travellers, until nightfall; or they risk falling off to a grisly end.

There you have it.

Not an exaggerated account or exceptional day. But run-of-the-mill encounters for literally millions of tired, mostly public sector workers, who take their lives into their own hands.

And if it’s bad on the footboard, cramped conditions on the inside run from dilapidated seating through poor ventilation to the prospect of being crushed at best or groped at worst… to say nothing of the danger of pickpockets.

This is only a snapshot of the plight of an estimated 1,900,000 commutersmaking an average 10,000,000 daily passenger trips in the Colombo Metropolitan Region (CMR). Add to their woes of personal discomfort the slowness of services in the CMR where trains average speeds of 20 kilometres an hour.

There are also interminable delays and no services on days when a plethora of trade unions cripple the national railway network with strikes. This is compounded by safety concerns on poorly maintained lines with weak points and ties, unguarded crossings, outdated signals and switching systems, and crumbling railway infrastructure.

And despite the recent importation of locomotives and coaches, Sri Lanka Railways’ (SLR) rolling stock is largely decrepit.

Some locomotives such as the legendary fleet of General Motors powered EMD G12 Class M2s are over 65 years old, imported from Canada under the Colombo Plan in the mid-1950s by the iconic General Manager of Railways B. D. Rampala MBE. Most short haul commuter trains have no toilets and facilities in all but a few stations lack basic sanitation.

It was the state of play when a previous government under its erstwhile Western Region Megapolis Transport Master Plan (WRMTMP) decided that a light rail transit (LRT) system, to be constructed in partnership with the Japanese government and Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA), would be a panacea to alleviate an unbearable burden.

The proposed LRT, to be completed with official developmental aid worth US$ 1.8 billion, would ease unavoidable traffic congestion that accompanied burgeoning rural development in metropolitan Colombo, which is an unplanned city.

But the WRMTMP with its LRT in 2016 had a plan to address the plethora of issues compounding congestion, inconvenience and hazardous transport options.

The six elevated line project would entail a circular route of 74.1 kilometres (a pilot phase would see 21 stations along 21 km – these numbers varied between 2017 and 2019) and encompass the densely populated boroughs of Colombo plus dormitory towns on the urban periphery that traditionally played hostel to the commercial capital’s working populace.

But a change of government in November 2019 saw the LRT project being unilaterally cancelled by the new regime at the stroke of a pen – an arbitrary letter from the president to the presidential secretary sans cabinet instrumentality – that was to cost Treasury coffers almost Rs. 6 billion in damages, loss of face with Japan and JICA, and Sri Lanka being brought into international disrepute.

The plight of commuters persists. But the country’s elites including politicos swan around in state convoys funded by taxpayers, travelling in comfort and safety, ignorant of their subjects’ perils.

And it is only recent governmental moves to revive the aborted LRT project that indicate solutions to the hoary issue may be on the fast track again.