Dr. Tilak Dissanayake

Committed to care

Q: What influenced your decision to pursue medicine in Australia?

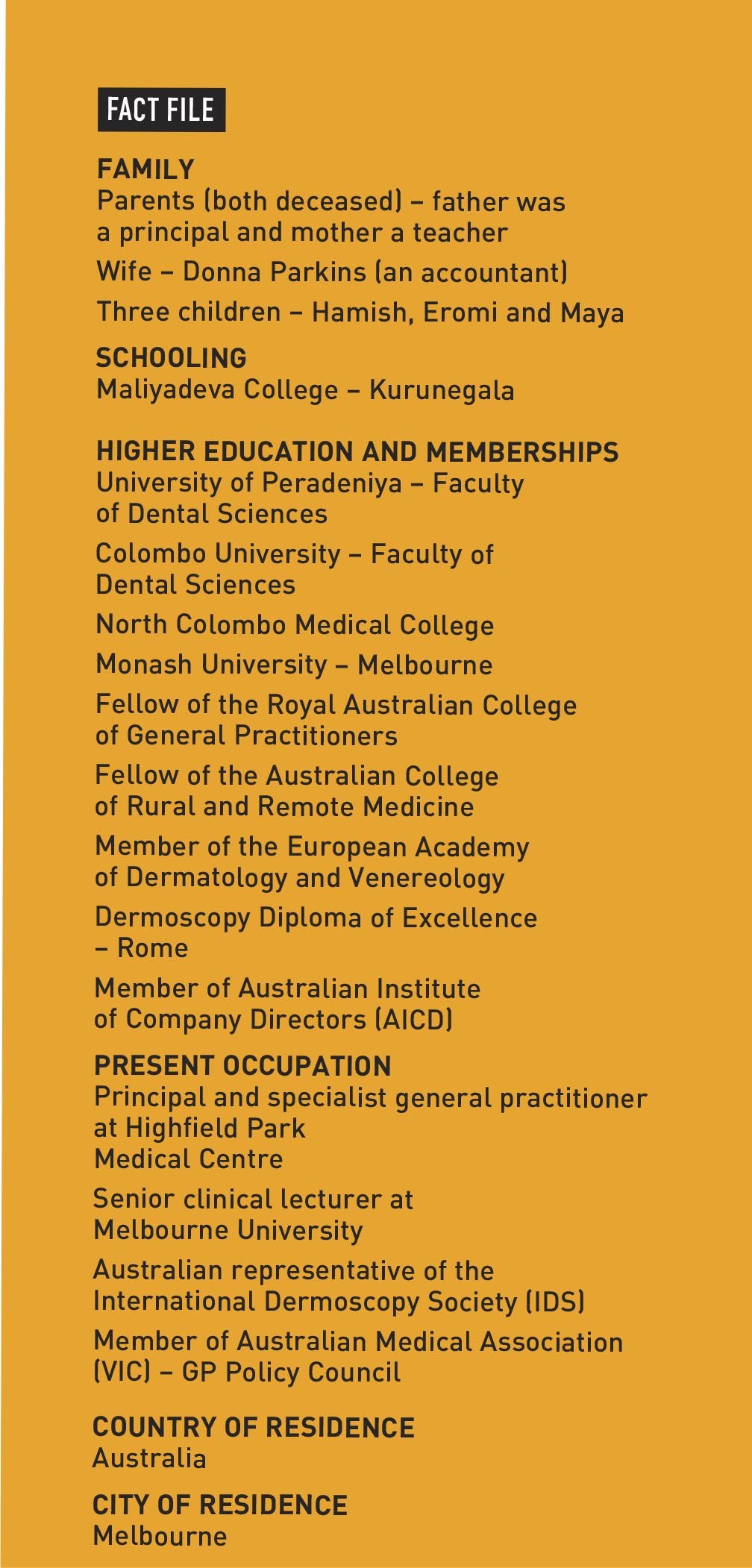

A: After completing my advanced level examinations, I was admitted to the Faculty of Dental Sciences at Peradeniya University and later to the University of Colombo, having missed the medical school cutoff by one mark. I was then accepted by North Colombo Medical College, Sri Lanka’s first private medical institution.

Medicine had been my passion but civil unrest and university closures disrupted my studies, and led me to relocate to Australia. With support from an Australian diplomat in Colombo, I moved to Melbourne, where I was accepted to study at Monash University’s renowned medical faculty.

My training was further enriched at the Alfred Hospital, which is an internationally recognised centre for trauma, transplant and burns care.

Q: What motivated your shift to rural general practice?

A: After a year of vascular surgical training at Austin Hospital and teaching anatomy at Monash University, I saw the need for medical services in remote areas. Coming from a regional background myself, I felt a strong connection to rural communities and their healthcare challenges.

I was offered a role as a Visiting Medical Officer at a hospital and a solo general practitioner in rural New South Wales (NSW). What was meant to be a 12 month opportunity turned into 12 years of service, allowing me to make a lasting impact on the community’s healthcare.

Q: How has your involvement with the Rural Doctors’ Network and Australian Medical Association (AMA) shaped your perspective on healthcare policies?

A: Serving as a member, vice president and eventually president of the Rural Doctors’ Association of NSW reinforced my belief that quality healthcare shouldn’t be limited to cities. This role enabled me to implement policies to improve healthcare access in rural communities.

As a Councillor of the Australian Medical Association (AMA), I advocated for national healthcare policies and addressed rural health challenges. In 2008, I became the first Sri Lankan elected to local government in New South Wales, where I used my role to address regional medical issues.

Although I left rural NSW over 13 years ago, I remain committed to advocating for better regional healthcare policies.

Q: What inspired you to establish Highfield Park Medical Centre – and how has your approach to skin cancer evolved?

A: I founded the practice in 2012 to provide medical care while supporting my family. It has since grown to serve over 10,000 patients in Camberwell, Melbourne.

With training in plastic surgery and dermatology, and regional experience, my approach to skin cancer care has evolved. My commitment to the field led to my appointment as one of three Australian doctors in the International Dermoscopy Society (IDS).

Q: What changes do you believe are still needed to improve rural healthcare in Australia?

A: Rural doctors are the backbone of Australia’s regional communities but recruitment and retention remain major challenges. Incentives are crucial to build a skilled medical workforce.

Despite substantial revenues from mining and agriculture, there’s a pressing need for cohesive and comprehensive healthcare in these communities. This requires focussed efforts to ensure that rural areas have the medical resources they need.

Q: How do you think Sri Lanka’s rural healthcare system compares with Australia’s? And what lessons can be learned from each other?

A: Sri Lanka would benefit from a national medical board to standardise medical practice and ensure that all doctors meet a unified standard. It would also facilitate ongoing education and professional development.

Sri Lanka’s compulsory rural training for doctors fosters early exposure to underserved communities, building empathy and hands-on experience.

In contrast, Australia’s elective rural placements result in an oversupply of doctors in metropolitan areas and a shortage in ageing rural populations. A more structured approach in Australia could help address this imbalance.

Q: Do you see emerging concerns in dermatology and skin cancer prevention in Sri Lanka that need more attention?

A: While Sri Lankans have higher melanin levels offering some degree of natural sun protection, global warming increases the risk of skin damage. Sun safety awareness and UV protection should be priorities to prevent complacency.

Limited access to advanced medical technology makes early skin cancer detection challenging, emphasising the need for prevention over reactive care. Expanding dermoscopic technology – which is crucial for early diagnosis – requires funding and wider accessibility to improve skin cancer outcomes in Sri Lanka.